Generative Modelling Part 4 - Text to Image Synthesis

/ 13 min read

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on my LinkedIn (click here) on August 15, 2018.

Long Post Alert!

TLDR; Generating images from text descriptions. See the result at the bottom of this post.

Introduction

This is the 4th instalment of ‘On Generative Modelling’ series. If you haven’t read my previous articles, go check them out: part one, part two, and part three. Each part has a different topic from the other, so feel free to jump to whichever part you want.

Also check my other series called ML.Rand() series :

- part1, Synthetic gradients and decoupled neural interfaces

- part2, Learning to learn (meta-learning)

- part3, How to build a mind-reader machine

- part4. Building machines with navigational abilities

In this article, we will continue our discussion about generative modelling; but now we have a special topic: text-to-image synthesis. I’ve been working on this very topic since a year ago for my bachelor’s thesis. So I wish to take this opportunity to share and communicate what I’ve been doing since I started the project and the progress that I’ve made on the subject. Consider this as a ‘simplified’ write-up of my work. I hope you enjoy it.

What is it that you’re working on?

If you’ve been paying attention to my posts, you’ve probably noticed it. I’ve talked about my work briefly in my first article of generative modelling series. I’ve been meaning to build an automated text to 3D model generator but a lot of things had happened so I decided to let it go. With the same spirit, I changed the topic and my objectives to only create 2D images from text descriptions. My work is not new nor innovative in any way, I just found it exciting and it is still an open problem in the research community. It’s based on Reed et al works in 2016 [1], so I’m ‘a little bit’ lagging behind. (Cut me some slack, okay! LOL)

Lots of researchers called it text-to-image synthesis.

See, in the context of visual, several deep learning models have been developed to create ‘artworks’ automatically, e.g Inceptionism [3] and Perceptual Losses[4]. Automated image generation/synthesis will be useful to develop an interactive computational graphic design, image fine-tuning, and perhaps even animation. Traditionally, computer is able to produce images by using handmade algorithms. But as you might have known, the result would be pretty much abstract, random, and full of patterns as it is limited by the algorithm itself.

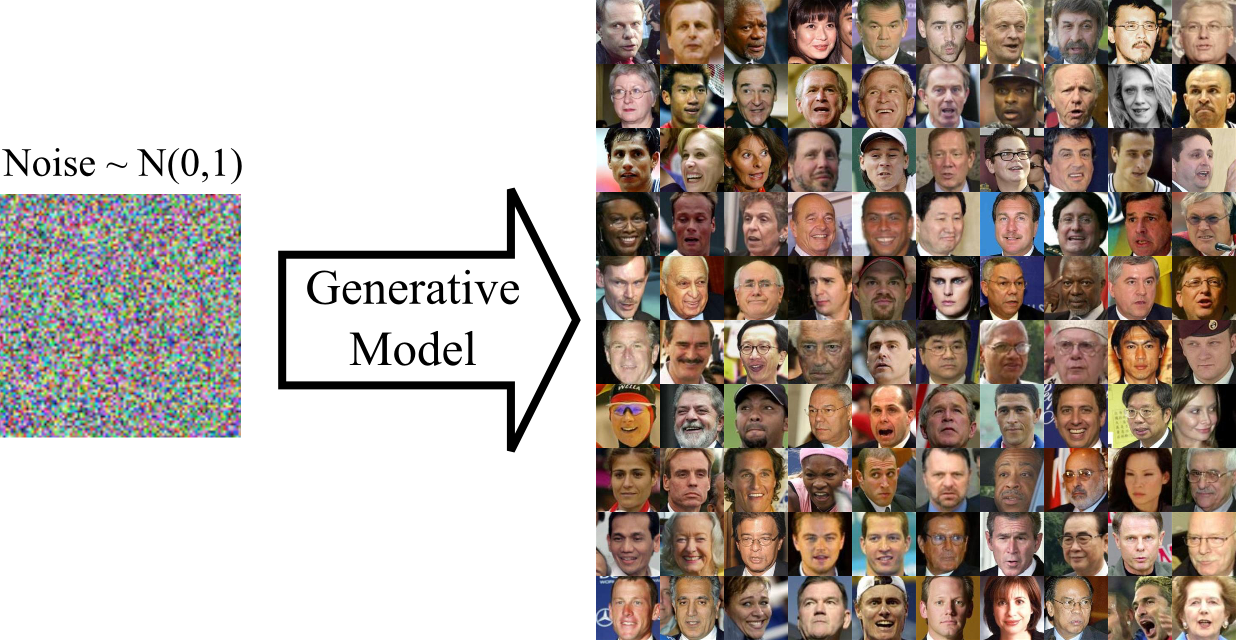

Generative modelling can be used to attack this problem. Various generative modelling technique/models including Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Generative Moment Matching Networks (GMMNs). Auto-regressive Neural Network, and real NVP have been widely used to generate samples (images).

Various research has shown that data generation process could be improved and controlled by conditioning the process with external information e.g tags. In the case of image, we can control the generated image by its properties including intensity, shape, and colour [5, 6].

On the other hand, natural language could be an alternative to control image generation process [1]. With natural language, we could describe the data(image) that we want to produce ‘easily’.

Text-to-image synthesis is kind of the holy grail of computer vision, since if an algorithm can generate truly realistic images from mere text descriptions, we can have a high confidence that the algorithm actually understands what is in the images, where computer vision is about teaching computers to see and understand visual contents in the real world. - Huang, H., Yu, P. S., & Wang, C. (2018)

Text-to-image synthesis is not an easy task to solve. But with the recent development of text representation and image synthesis techniques, it’s been possible to produce images from mere text description.

How to Build Such a System?

Text-to-image synthesis is a reverse captioning problem (image-to-text): given an image, a text description of the image must be produced. If you think about it, the problem can be seen as a translation task where the same semantic is encoded into two different languages: image and text. So we want to translate text-to-image: given a text description, an image which matches that description must be generated.

But translating image-to-text or text-to-image is different from text-to-text in the sense that text-to-text translation has a smaller result space. When we translate a given sentence from one language to another language (text-to-text), there would be a relatively ‘small’ number of ‘valid’ results corresponding to the text.

It is different from text-to-image or image-to-text task where a huge amount of results might exist. For example, the following sentence “A gang of elks standing near the bank of a narrow river” will result in lots of valid images as it is unclear how many elks are in the ‘gang’. Moreover, the description of the background is uncertain.

However, text-to-image synthesis itself can be considered as a harder problem than captioning (image-to-text). This is mostly because language structure which is inherently sequential so that the formation of the next word could be conditioned on the previously generated words.

There are two main problems that we need to solve in order to build a text-to-image synthesis system. First, we need to represent the given sentences as vectors which capture important features. Second, we need to use these vector representations to generate images by using generative models.

How to convert sentences into vectors?

We could use text embedding. There are (at least) three representation techniques which are really promising:

-

Skip-thought [7], is an encoder-decoder model which is trained on a corpus of novels across 16 genres. The encoder maps the input sentence to a sentence vector and the decoder generates the sentences surrounding the original sentence resembling skip-gram model in the sense that surrounding sentences are used to learn sentence vectors. Skip-thought aimed at producing generic, distributed sentence representations that are robust and perform well in practice.

-

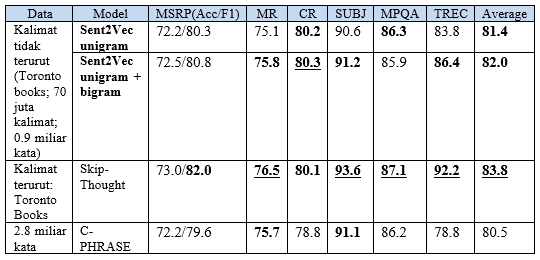

Sent2Vec [8], is a ‘relatively’ simple model that offers an incredibly well performance in multiple benchmarks including but not limited to paraphrase identification (MSRP), subjectivity classification (SUBJ) and polarity of opinion(MPQA). See Table I below for the details. In generals, there are two recent trends in text understanding research (or distributed representations of text). The first one employs models with high complexity e.g RNN, LSTM, Neural Turing Machines or other attention-based models. The second one is making use of matrix factorizations (bilinear model) with shallow architecture. This kind of model is able to be trained on a huge amount of data at a higher speed. Sent2Vec is one of those ‘shallow’ models. It is very efficient with the complexity of O(1) to process each word in a sentence into vectors at inference/training time. After comparing this technique with skip-thought, I can safely say that it’s somewhat true. When I tried to infer +-80.000 sentences using skip-thought, it took me 12 hours++ to complete the task. Meanwhile, the same task can be completed within 15 minutes by using Sent2Vec.

-

Char-CNN-RNN [9]; many researchers claimed that this model is superior to other techniques for multi-modal task where image and text are involved the likes of text-to-image synthesis. It’s because the model is trained using text and image jointly. In fact, this model was employed in the GAN-INT-CLS model where the first text-to-image synthesis model introduced by Reed et al (2016).

Table I: Performance comparison of Sent2Vec (unigram/bigram) accross multiple supervised evaluations. Source: Personal Gallery, adapted from Pagliardini et al (2018)

What about converting the vectors into images?

For the generation part, we need a kind of model that can make use of the text representations and convert the vectors into images. The right class of model that can be exploited is generative models. Among other generative models, GANs have shown incredible results on MNIST, CIFAR-10, CUB-200, and LFW datasets with relatively higher inception scores. The produced samples are also much sharper than VAE’s results. That’s why I chose GANs for my bachelor’s thesis. Well, there are actually some other reasons:

- GANs produce ‘better’ result than other generative models (sharp and compelling)

- They do not require a likelihood function to be specified. So they don’t have to learn the density of data explicitly. This is an advantage because sometimes when the data distribution is complex, we couldn’t find the density so it could be a problem when we were to learn it explicitly.

- GANs are flexible in terms of its loss function and its topology.

However, it is important to note that despite all its strength. GAN is well-known as hard to train. Its training process is very unstable and requires a lot of tricks to get a good result. Moreover, GAN also suffers from the mode collapse. It’s a phenomenon where the generator network is only able to produce samples from some of its data mode. In other words, the generator learns to produce samples with extremely low variety. This is because, in the original formulation, the discriminator network is only focused on spotting fake samples/true samples. So it doesn’t need to consider the variety of synthetic samples. Many methods have been proposed to address this mode collapse problem including minibatch features[10]. In my bachelor’s thesis, I attack this problem by using Wasserstein GAN.

To make the implementation simpler, the kind of GAN that I employed was a direct GAN, where there are only a generator and a discriminator in the architecture. While it’s easier to implement than hierarchical methods (e.g SS-GAN, LR-GAN) or iterative methods (e.g LAPGAN, StackGAN) it’s also still capable of producing good-enough (acceptable) results.

To make the problem simpler, I created several constraints for the training data:

- Background/Foreground should be distinguishable.

- The images contain only 1 object.

- The object is a structure e.g number, face, bird.

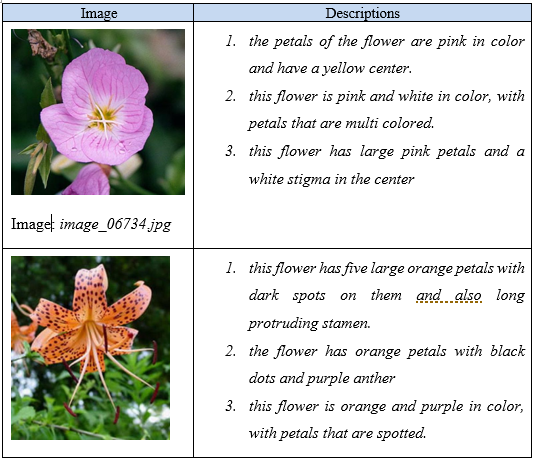

Datasets that met those criteria are Oxford-102 Flowers Dataset and Caltech-UCSD Birds 200-2011. You can also use Behance Artistic Media (BAM) Datasets or any other available datasets as you please. But I used the Oxford Flowers Dataset only. Descriptions for each image is taken from Reed et al (2016), and after some pre-processing, we got pairs of image and descriptions (up to 10 descriptions per image) as shown in Table II.

Table II: Samples of the training data. Source: Personal Gallery.

Training Setup

One of the objectives is to compare the variety of generator architectures and how it affects the generated images. There are three types of generator architecture employed: small, normal, and deep. I also wanted to know how different text embedding techniques affect the generated samples so I decided to use Sent2Vec (bi-gram + uni-gram) and Skip-thought (combine-skip: bi-skip + uni-skip) vectors in separated experiments.

The model was trained on a machine with this following specifications:

- Processor : 2 x Intel® Xeon ® @ 2.30GHz,

- RAM : 14GB

- GPU : NVIDIA Tesla K80, 24GB GDDR5

Adam optimizer is used for training with beta1 = 0.5, and the model is trained for a total of 175 epochs (as of now, will be trained for more in the near future) with a batch size of 64. For the Sent2Vec experiment, I used 700 vector dimension for uni-gram and bi-gram. Then the vectors are concatenated to noise with a dimension of 100 resulting in 1500 dimension of vector input. As per the Skip-thought experiment, I combined the uni-skip vector and bi-skip vector resulting in a combine-skip vector of 4800 dimension. After the noise dimension was added, the vector input would be a dimension of 4900.

Result

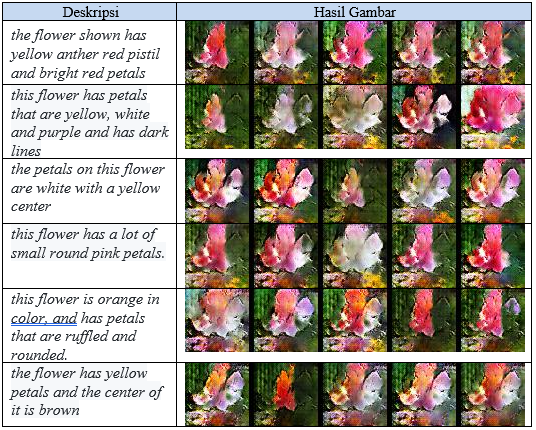

After roughly 10 hours of training, it reached 100 epoch. Let’s take a look at the following table of Sent2Vec experiment results at epoch 100.

Table III: Generated images at epoch 100. Source: Personal Gallery.

As you can see, the results are really bad at epoch 100. There’s not much variation, and the images do not correspond with the text descriptions at all. So I decided to run 15 more epochs.

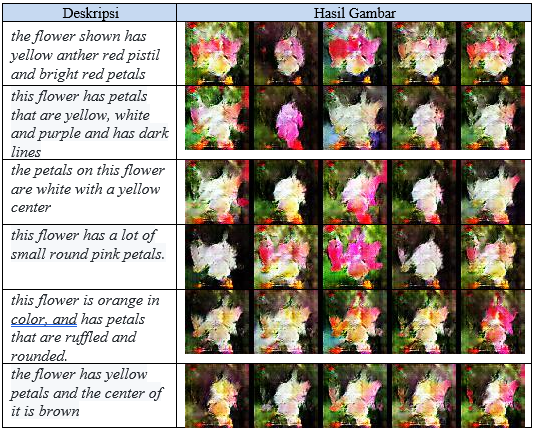

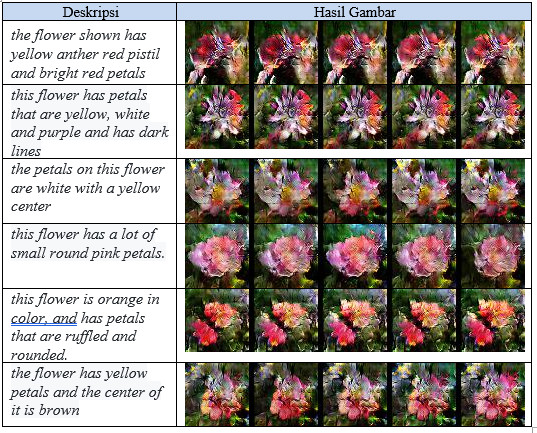

There is not much of improvement after 115 epoch but now each object is clearer than before. In each image, the border is sharper, the background and the foreground is more distinguishable. And after 60 more epochs… voila.

It’s much better now. We can see that each image is a little bit corresponding to its text description. Let’s take a look at the fourth description, the generated images have small round pink petals as the description says. And in the third description: “The petals on this flower are white with a yellow centre”, as you can see, it produces flower images with a yellow centre in each image. The model has learned about colour, and shape from text descriptions. It’s really cool! :D

Conclusion

In this work, I present Generative Adversarial Networks and their application in the problem of text to image synthesis. I obtained relatively good results from the experiments but I think there’s a lot of things that could be improved. I will definitely be adding more of my experiment results in the future.

IMPORTANT NOTES

I don’t know if you noticed it, but my Sent2Vec model above suffers from a common problem in GAN called mode collapse. A collapsed GAN produces low variety samples because the Generator is collapsing into narrow distribution that only covers some portion of data distribution.

Wasserstein GAN (WGAN) promises to remedy that problem above by using Wasserstein Distance (Earth-Mover Distance or EM for short). If you think of the probability distributions as mounds of dirt, the EM distance describes how much effort it takes to transform one mound of dirt so it is the same as the other using an optimal transport plan. Here, we also restrict the range of the weights, to guarantee Lipschitz continuity. But, will WGAN cure my model? let’s see :D

References

-

[1] Reed, S., Akata, Z., Yan, X., Logeswaran, L., Schiele, B., & Lee, H. (2016). Generative adversarial text to image synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.05396.

-

[2] Huang, H., Yu, P. S., & Wang, C. (2018). An Introduction to Image Synthesis with Generative Adversarial Nets. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.04469.

-

[3] Mordvintsev, A., Olah, C., & Tyka, M. (2016). Inceptionism: Going Deeper into Neural Networks. Retrieved 10 30, 2017, from Google Research Blog: http://googleresearch.blogspot.co.uk/2015/06/inceptionism-going-deeper-into-neural.html

-

[4] Johnson, J., Alahi, A., & Fei-Fei, L. (2016). Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. European Conference on Computer Vision (pp. 694-711). Springer.

-

[5] Dosovitskiy, A., Tobias Springenberg, J., & Brox, T. (2015). Learning to generate chairs with convolutional neural networks. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, (pp. 1538-1546).

-

[6] Kulkarni, T. D., Whitney, W. F., Kohli, P., & Tenenbaum, J. (2015). Deep convolutional inverse graphics network. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, (pp. 2539-2547).

-

[7] Kiros, R., Zhu, Y., Salakhutdinov, R., Zemel, R. S., Torralba, A., Urtasun, R., & Fidler, S. (2015). Skip-thought vectors. arXiv: Computation and Language, 3294-3302. Retrieved 10 31, 2017, from https://arxiv.org/abs/1506.06726

-

[8] Pagliardini, M., Gupta, P., & Jaggi, M. (2017). Unsupervised learning of sentence embeddings using compositional n-gram features. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.02507.

-

[9] Reed, S., Akata, Z., Lee, H., & Schiele, B. (2016). Learning deep representations of fine-grained visual descriptions. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, (pp. 49-58).

-

[10] Salimans, T., Goodfellow, I., Zaremba, W., Cheung, V., Radford, A., & Chen, X. (2016). Improved techniques for training gans. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, (pp. 2234-2242).