ML.rand() Part 4 - Building a Machine with Navigational Abilities

/ 8 min read

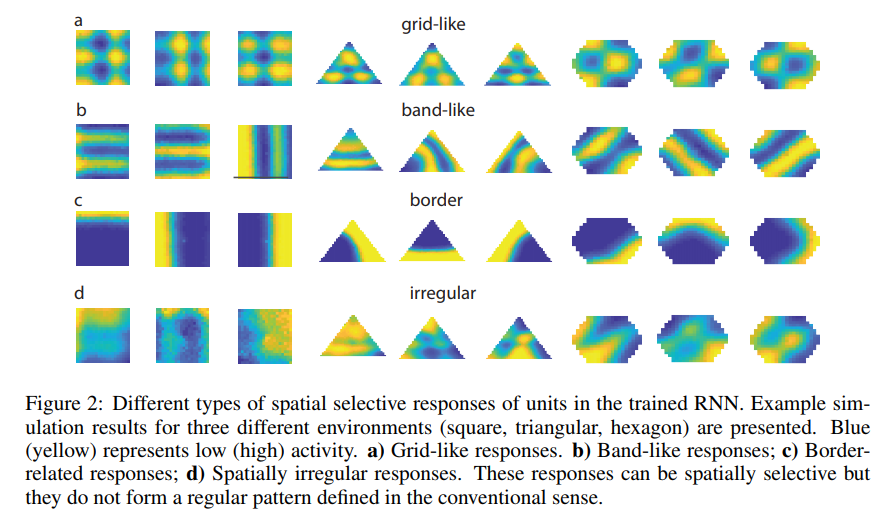

TLDR; We could train an RNN to perform a spatial navigation task, and then study the responses of the model neurons in the RNN of which we could find many properties reminiscent of neurons in the mammalian entorhinal cortex (EC): grid cells, border cells, etc.

Introduction

Welcome to the 4th instalment of ML.rand() series. In a previous article we’ve learnt to build an artificial agent which is capable of simulating the Theory of Mind with meta-learning. Now, we’re going to be exploring the possibility of building a machine with navigational abilities. I hope you enjoy it.

Note: I assume that the reader is familiar with the definitions and techniques of machine learning (and a bit of neuroscience. But I think it would be understandable without).

Most animals, including humans, are able to flexibly navigate the world they live in – exploring new areas, returning quickly to remembered places, and taking shortcuts. Indeed, these abilities feel so easy and natural that it is not immediately obvious how complex the underlying processes really are. In contrast, spatial navigation remains a substantial challenge for artificial agents whose abilities are far outstripped by those of mammals. - Banino, Andrea et al., DeepMind

How do we know where we are in space?

Some people have a great sense of direction. Even after wandering around town all day, they still know exactly how to get back. And here I am. I am that kind of person who always has to open Google Maps every time I want to go someplace.

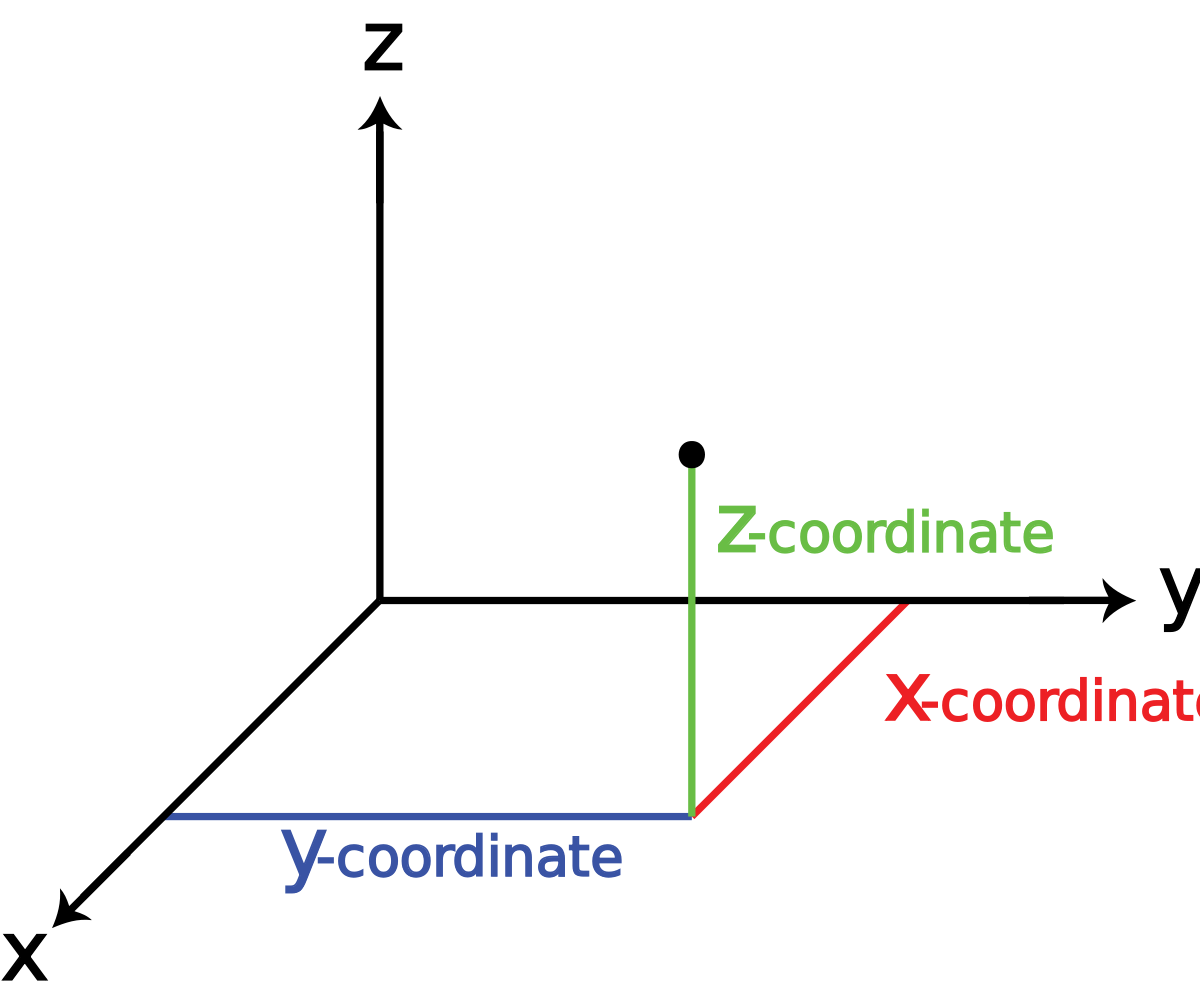

But believe it or not, although our sense of direction varies, all of us have an idea of what our surroundings look like and where we are located within them; We’re all posses the same capability. The question is, how do we know where we are in space? Not space ‘space’, but this following space:

It was actually first suspected in 2005 that there is something within our brains that facilitate spatial navigation known as the Grid Cells (the suspicion is actually could be traced back to the 50s). It’s like a GPS system within our bodies. In fact, Grid Cells are not the only cells that enable us to navigate.

As it is, our brains contain a spatial map of the world. What neuroscientists mean by this is that there are brain cells that fire depending on where we are and where we’re going. There are different types of these cells, each with a unique role. Together, they enable us to navigate the crazy world we live in [3]. There are at least five cells that I know of as to date:

- Place Cells. They represent an abstract idea—place—that most of us think of as a high-level concept. Each cell fired whenever we were passing through a particular place, like one of those big “YOU ARE HERE” markers on a map. Read More.

- Grid Cells. They enable the brain to calculate the distance and direction to the desired destination. Read More.

- Head-direction Cells. They fire based on the direction our heads are facing, thus encoding where we’re going. Read More.

- Border Cells. They tell us when we’re near a wall. Read More.

- Speed Cells. They fire depending on the speed at which we’re moving. Read More.

- etc.

This internal navigation system evolved in mammals over tens of millions of years. For a more detailed information about this ‘spatial map inside our heads’, please visit this link.

But are these cells actually necessary for navigation?

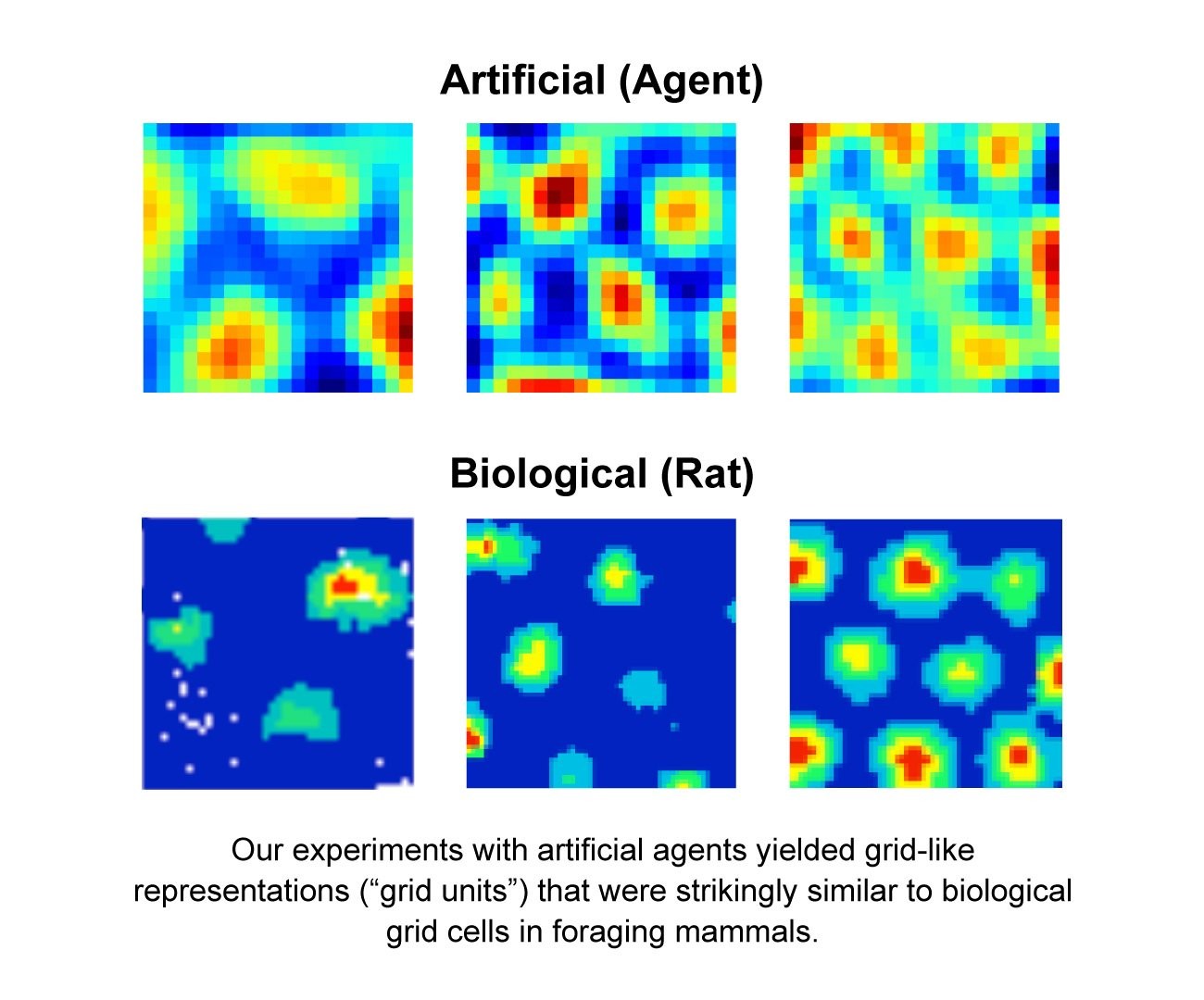

A team from DeepMind (Banino, A. et al, 2018) tried to find out the answer and they have published the result on Nature (visit this link). As you might have guessed, the answer is ‘yes’, they are necessary. The grid-like representations emerged within the trained LSTM networks and the result is consistent with the neural activity patterns observed in mammals as shown in the following figure taken from DeepMind’s blog:

They trained a grid cell network that consists of a recurrent layer (LSTM, 128 units), a linear layer (implements regularization, i.e Dropout with prob. of 0.5), and an output layer. At each timestep t, the grid cell net receives the egocentric linear velocity v, and the sine and cosine of its angular velocity phi. So the input to the LSTM layer is the vector [velocity(t), sin(phi(t)), cos(phi(t))].

There are two ground truths used, namely the place cell and the head-direction cell. For a given x position, place cell activations c were simulated by the posterior probability of each component of a mixture of two-dimensional isotropic gaussians. For a given facing angle phi, the head-direction cell activations h were represented by the posterior probability of each component of a mixture of Von Mises distributions with concentration parameter k (a fixed value of positive scalar).

The network then trained using supervised learning technique to simulate a rat trajectories of duration T. The trajectories are obtained using a rat-like motion model[8]. The parameters of the grid cell network are trained to minimized this following loss function:

Which is the cross-entropy between the network place cells predictions, y and place cells target (synthetic) c. (from i = 1 to N), and the cross-entropy between the network head-direction predictions z and head-direction target (synthetic) h. (from j = 1 to N).

P.S The gradients calculated using backpropagation through time. Read More.

Moreover, after the above grid network was incorporated into a larger network that was trained using deep reinforcement learning, it exhibited goal-finding abilities with high levels of performance by reaching the goal more frequently than either control agents or human agents, even in procedurally generated multi-room environments[1]. When we remove the grid network, the agent will struggle to get around efficiently. This behaviour supports the idea that grid cells are important to plan and calculate a path. The agent also has an ability to exploit shortcuts to reach the goals automatically, performance exceeded that of conventional Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) techniques and previous deep reinforcement learning approaches such as [5, 6, 7].

Interestingly, the DeepMind’s team wasn’t the only one who attempted to answer the open question.

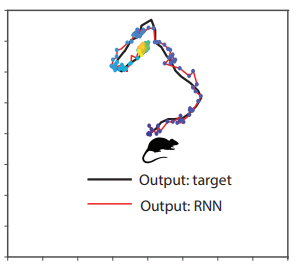

Simultaneously, a group of researchers from Columbia University (Cueva & Wei, 2018) embarked on the same journey to understand neural representations within our brains with a different scope (visit this link). They trained an RNN with 100 recurrently connected units that receives velocity data and heading direction to perform some navigation tasks in 2D arenas. The goal of the training is to make the responses of the two output neurons (x and y coordinates) accurately represent the animal’s physical location as shown in the following figure (Source: Cueva & Wei, 2018):

Surprisingly (or not?), Grid-like spatial response patterns were also emerged in the trained networks along with the border cells, band-like cells, etc, ‘similar’ to what Banino, A. et al, 2018 have found.

However, as opposed to DeepMind’s findings where they found grid-like whose firing pattern closely resembles rodent grid cells which typically show hexagonal firing patterns across different shaped environments, the Columbia team found a periodic firing that conformed to the shape of the enclosure (e.g rectangular grids in a square environment and triangular in a triangular environment) [4] as you can see in the above figure. But in both studies, when regularization (i.e Dropout) of the network is not used during training, the trained RNNs no longer resemble the EC.

If you’re interested in a more detailed explanation of how things work + methods employed by the authors you can check the paper by DeepMind here, and the Cueva & Wei, 2018 here.

Final Thought

It’s exciting to see works like these; they integrate AI and neuroscience. I hope more things will emerge. These works gave us some hints that artificial neural networks, which are themselves inspired by biology, might be used to explore the workings of the human brain. This is interesting because now ‘valuable’ insights also flowing back from AI research to shed light on open questions in neuroscience. However, finding brain-like features in a neural network isn’t new as we also find these in ANN that process and categorise images, for example. What’s new here is that it’s the first time we’ve done it with grid cells.

References

-

[1] Banino, A., Barry, C., Uria, B., Blundell, C., Lillicrap, T., Mirowski, P., … & Wayne, G. (2018). Vector-based navigation using grid-like representations in artificial agents. Nature, 1.

-

[2] Cueva, C. J., & Wei, X. X. (2018). Emergence of grid-like representations by training recurrent neural networks to perform spatial localization. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.07770.

-

[3] http://www.brains-explained.com/how-the-brain-encodes-space-and-place/

-

[5] Oh, J., Chockalingam, V., Singh, S., & Lee, H. (2016). Control of memory, active perception, and action in minecraft. arXiv preprint arXiv:1605.09128.

-

[6] Kulkarni, T. D., Saeedi, A., Gautam, S., & Gershman, S. J. (2016). Deep successor reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.02396.

-

[7] Mirowski, P., Pascanu, R., Viola, F., Soyer, H., Ballard, A. J., Banino, A., … & Kumaran, D. (2016). Learning to navigate in complex environments. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.03673.

-

[8] Raudies, F., & Hasselmo, M. E. (2012). Modeling boundary vector cell firing given optic flow as a cue. PLoS computational biology, 8(6), e1002553.