ML.rand() Part 3 - How to Build a Mind-Reader Machine (Theory of Mind)

/ 15 min read

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on my LinkedIn (click here) on May 10, 2018.

Introduction

This article is part of a series called ML.rand(), a brand-new series where we can discuss virtually anything about Machine Learning, randomly. If you haven’t read my previous articles on this series go check them out here: random ml series.

Also check my other series called On Generative Modelling: generative modelling series.

In this article, we’re going to learn and explore:

- What is Theory of Mind?

- Correlation between Theory of Mind and humans ability to socialize.

- Does machine has a Theory of Mind?

- Is there any chance for us to build a machine with a Theory of Mind?

- How to build one?

Just a heads up, this is going to be a long post (like, really long) and it will be divided into two sections. The first section mainly address the 1st - 3rd of the above points, and the rest of the points will be explored in the second section.

If you’re already familiar with the basic of Theory of Mind concept, you can jump and scroll all the way down to the second section at the bottom. But I would highly encourage you to read it in order, as the first section plays an important role in building the connection among the Theory of Mind, our critical ability to interact with others, and a ‘mind-reader’ machine.

Now, let’s get started. I hope you enjoy it.

SECTION 1

Where are all the cool droids and humanoids that science fiction promised us?

What a time to be alive! This is an exciting time to be working in so called ‘Artificial Intelligence’ field; The hype is real. The progress is real. The industry adoption is real.

Actually, AI is only real in the sense that it’s a REAL field of study. Well, at least to me, for now. It depends on our opinion for the term ‘real’, really.

But hey, we’ve seen a lot of progress related to this field (Yay!). Some techniques perform really well in computer vision area: the Large Scale Visual Challenge problem. In fact, it already had superhuman abilities in the said challenge since 2015. The results of Neural Machine Translation now is good enough for us to understand what’s being written. The conversational agents are rising up. Also, don’t forget about the progress in self-driving cars. One of the latest result even able to make self-driving cars cruising on less travelled roads. What else? Oh, AlphaGO! which is quite interesting as it doesn’t even need human help to beat us anymore.

In other narrow fields, AIs are still catching up to humans. But what about the broader fields? It’s clear now that we’re not going to have R2D2-type of droids in the near future, aren’t we?

But just how far off was them?

Well, for starters… At least, we need them to understand what we speak, and be able to communicate with us via natural language so we need the following technologies/systems: speech recognition, NLP, speech synthesis, information extraction, whatever you name it. We also need them to be able to see, recognize objects, etc. Not to mention the robotics parts and the control system.

There’s a lot of progress in those areas, but I personally think that we’re not quite there yet.

Speaking of smart robots, what struck me the most about these robots(R2D2, C3PO, etc) is the ability to socialize with us. They are smart (and cool) and at the same time, are capable to work together with us to achieve goals.

This, my friend, is probably what missing from current AI design.

Theory of Mind

First of all, I want to ask you this question: What’s the difference between robots and humans? (Put the materials aside).

Hint: (To some extent) robots don’t have what we called the ‘Theory of Mind’. (or do they? hmm?)

Theory of mind [1] refers to the ability to attribute mental states such as beliefs, desires, goals, and intentions to others, and to understand that these states are different from one’s own.

It is our unique ability to reason about what is going on inside other people’s minds, including what they want (desires), what they know (knowledge), and what they think is true based on their prior experience (beliefs).

A theory of mind makes it possible to understand another person’s knowledge, understand emotions, infer intentions, and predict behaviour. It enables us to be a ‘mind-reader’.

The ability to ‘read’ others’ minds is critical to human cognition and social interaction; it allows us to build and maintain relationships, communicate effectively, and work cooperatively to achieve common goals because as we all know, normal social interactions depend upon the recognition of other points of view.

This capability is probably one of those things that we take for granted; Recognizing other minds comes effortlessly for humans, but it is no easy task for a computer.

False-belief Task

A commonly used task to measure Theory of Mind is the false-belief task. This test is designed to measure whether or not a child is able to reason about other people’s mental states. Imagine this following scenario:

- You have a box of sweets. Ask a child what he/she thinks is inside the box. He or she will likely respond “Sweets.”

- Open the box and show him/her that there is a ring inside while saying “See.. it’s actually a ring! Not sweets.”, then close the box.

- Then, you bring another kid into view e.g John, and say “John has never ever seen inside this box.” What does John think is in the box? Sweets or a Ring? (Hint: sweets)

As adults, we know that John has a false belief about what’s in the box. So do the children who have developed Theory of Mind. They will understand that John holds a different understanding than them because he did not see what’s in the box; They will respond that John thinks there are sweets in the box.

However, children often have trouble holding two distinct perspectives. Those who have yet to develop Theory of Mind will mistakenly assuming that John holds same beliefs as they do.

Now you might ask.. Is it that important, Theory of Mind? why hasn’t it been a central focus of the AI development around the world?

Well, evidence shows that Theory of Mind is at the base of children’s social understanding, and the lack of components of Theory of Mind may compromise social development [6]. It means that Theory of Mind and social skills are tightly related. So it is safe to say that if we were to build a human-like robot that is inherently social and can interact naturally with people, our robots must have fundamental social skills including the attribution of beliefs, goals, and desires to other people: Theory of Mind [3].

It’s just that we haven’t the faintest idea of how to make machines with minds like ours.

Does a machine has a Theory of Mind?

Firstly, I am no philosopher so I can’t really give you any philosophical answers. Secondly, instead of answering whether or not a machine has a Theory of Mind (ToM) I would like to say that if we formulate the task in the right way, we can cast the problem of building ToM as a relatively simple learning problem and build a simple agent who has a (simple) Theory of Mind [2]. (Man, there’s a lot of ‘simple’ right there.)

In fact, in the following section, we’re going to be dissecting a newly released paper called Machine Theory of Mind and continue our discussion on how to build a machine with ‘mind-reading’ ability. It’s a fresh paper, which was published by a team (Rabinowitz, N. C., et al 2018) from Google DeepMind and Google Brain in February 2018 and believe me it is super cool.

By the by, if you’re really interested in a more structured, ‘philosophical’ answer on Computational Theory of Mind, you can check out this article.

SECTION 2

(I’d suggest skimming the paper first but this should all be understandable without.)

Building a rich, flexible, and performant Machine Theory of Mind may well be a grand challenge for AI[2]. So the authors limited the scope of their work only to figure out the best way of formulating the task of building Theory of Mind (ToM) into some learning problems. Essentially, the challenge of building ToM can be seen as a Meta-learning problem so the authors tried to formulate it as a Meta-learning task as follows: Basically, we want to train an observer agent, let’s call it agent A who can ‘understand’ another agent B by observing its behaviour. Of course, A will only get a limited access to B’s behaviour history; This is a resemblance of everyday human interaction. The goal here is to make A ‘understand’ B’s behaviour, and be able to predict B’s future behaviour. In the end, we will have an expert observer A, who can ‘mind-read’ the other agents with limited data.

Before we continue, let us stop and ask: what does it actually mean to “understand” another agent (or person)? let’s think about it for a moment; We often forget that minds are not directly observable. In everyday life, not once did we attempt to “understand” people we interact with by estimating their neuron’s activity or by inferring the connectivity of their prefrontal cortices, you know what I mean.

So what’s to “understand” mean, really?

Some argued that we rely on high-level models of other agents instead and represent mental states of others: Theory of Mind[2] so let’s stick to that argument. Thus, what we meant by understanding others is an attempt at representing mental states of others. As such, programming a machine with this capability is extremely challenging, to say the least, but of course not impossible.

Let’s get back to our observer agent A

Observer A is basically a Neural Network and from now on let’s call it the ToMnet. The ToMnet has been experimented in around 5 different ‘scenario’ with increasing complexity such as:

- Learning to approximate Bayes-optimal hierarchical inference over agents’ characteristics. (not discussed)

- Learning to infer the goals of an agent as well as how would they achieve the goals (balance costs and rewards). (will be discussed further)

- Learning to characterise different species of agent and finding the essential factors of how an agent different with the others. (not discussed)

- Implicitly learn to understand that deep RL agents hold false belief about the world. (not discussed)

- Learning to predict agents’ belief state and revealing agents’ false belief explicitly. The authors also show that the ToMnet can infer what different agents are able to see, and what they therefore will tend to believe, from their behaviour alone. (not discussed)

Time for some formalism

Let’s assume that we have a family of Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes (POMDPs) M. But as opposed to the ‘standard’ formalism, our POMDPs now only have state spaces S, action spaces A, and transition probabilities T, i.e Mi = (Si, Ai, Ti). The rest (reward functions, discount factors, conditional observation functions) will be associated with the agents rather than the POMDPs. It means that even when the agent was placed in the same POMDP, different agents might receive different rewards. Not only that, they will also see different amount of local surroundings. When the agents have full observability, we use the terms MDP and POMDP interchangeably [2].

Note: Here, we limit our POMDPs into only a single-agent POMDPs.

Additionally, we also have a family of agents A (look carefully, it’s italic. To make it different from action spaces A):

Where Ωi is its observation spaces, Ri and γi is its reward functions and discount factors respectively, ωi is its conditional observation functions, and last but not least is the resulting policies πi.

Note: the policies might be stochastic (scenario 1), algorithmic (scenario 2), or learned (scenario 3 - 5).

For a more detailed formalism, and how the setup and problem statement differs from the imitation learning, go check the paper out.

The architecture

Remember the task that we’re trying to solve? Yeah, the one where I introduce you the observer agent A at the beginning of section 2; We want to train an observer agent who is able to predict many agents whose rewards, parameterizasions, and policies may vary [2].

One thing to note here is that there is informational asymmetry, meaning that the student (the observer) is more resourceful in the sense that it knows more about the environment than its teacher (i.e the Agent Ai <- italic). Therefore, there is a systematic bias: its policy may be not optimal.

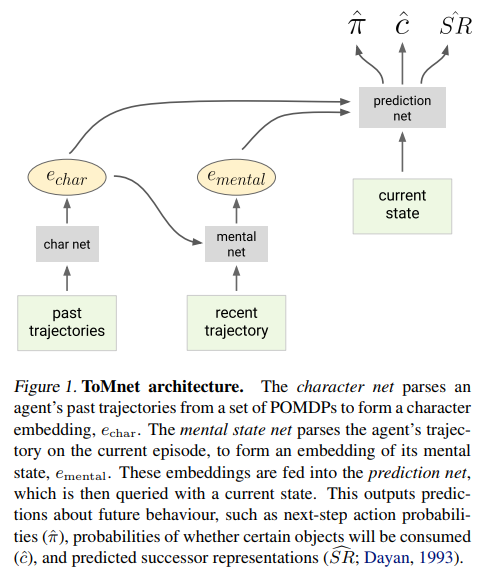

OK, now we’re ready to solve the task. We define a ToMnet as shown in the above figure where it composed of three modules: a character net, a mental state net, and a prediction net. You can see the definition of each net in the said figure.

The character net aims to characterise a presented agent, while the goal of the mental state net is to infer the mental state of the presented agent during the current episode. Lastly, the prediction net will be used to predict the subsequent behaviour of the agent by leveraging character and mental state embeddings[2].

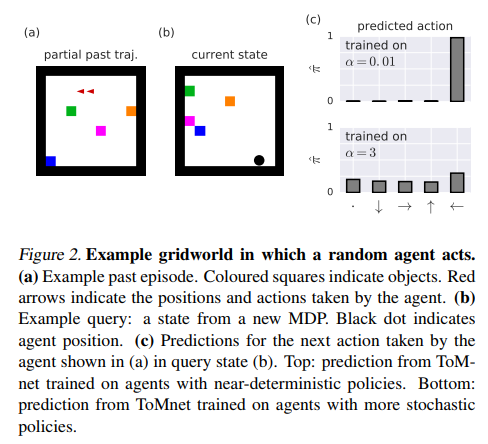

The POMDPs being used here are grid worlds with a common action space (up/down/left/right/stay) as depicted in the following figure.

The Experiments As we all know, there are five different scenarios used by the authors to demonstrate ToMnet. But here, I just want to explore the second scenario in which we train the ToMnet to be able to infer others’ goals (or ‘desires’).

We do this by deploying several species of reward-seeking agents with full observability as shown in figure 2a above in a 11x11 grid world which contains four different objects and walls placed in random locations. Every time an agent consume an object, it gets rewarded and the episode will be terminated. Since each agent has a fixed different reward function (as discussed in ‘formalism’ part earlier), a particular agent will receive a different amount of reward between 0 and 1.

However, every move taken by an agent will cost in -0.01, and -0.05 if it hits a wall. So they better be careful. That’s why the agents have to plan their behaviour carefully (here, they do so through value iteration), resulting in an optimal policies πi* with respect to their own reward functions [2]. Then, we train the ToMnet to observe these behaviours by providing an access to randomly past MDPs of each agent. With this information, the ToMnet will have to predict the agents’ future behaviour. There are three settings in this particular scenario:

- The ToMnet provided with a full trajectory of an agent on a single past MDP.

- We only provide partial trajectories of an agent history to the ToMnet.

- We apply a very high move cost to the agents.

In the first settings, the ToMnet’s predictions qualitatively matched the agents’ true behaviours and in the second settings, the ToMnet’s ability to predict increases because we increased the number of past observations (as expected). In other words, the more we know about someone’s history, the more likely we can predict his/her behaviours in the future.

Final Thoughts

Man, this is a long post. Told you though. I kind of had an idea to separate the sections into two articles but I don’t know why I kept writing on the same editor and here we are with a crazy long post, so sorry for that. Of course, there is a lot of things that we didn’t explore here, simply because I want to make this article as general as possible so I skipped over a few technical details. But it was rather hard to explain something with no technicalities whatsoever; God knows I tried. However, I’ve still got many things to learn.

So, Meta-learning, huh? time and time again, it has proven itself as a really powerful concept; now we can even build a system which able to model other agents by using meta-learning. The ToMnet itself is a flexible network, as shown in lots of experiments in the paper; It is able to learn to model different species of agents, whilst making few assumptions about the generative processes driving these agents’ decision making which is really cool.

I really want to see what’s next.

References

-

[1] Premack, David and Woodruff, Guy. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind? Behavioral and brain sciences, 1(4):515–526, 1978.

-

[2] Rabinowitz, N. C., Perbet, F., Song, H. F., Zhang, C., Eslami, S. M., & Botvinick, M. (2018). Machine Theory of Mind. arXiv preprint arXiv:1802.07740.

-

[3] Scassellati, Brian. (2000). Theory of Mind for Humanoid Robot. MIT Artificial Intelligence Lab. Link: http://groups.csail.mit.edu/lbr/hrg/2000/Humanoids2000-tom.pdf

-

[4] Margolis, Eric., Richard, Samuel., and Stitch, Stephen. (2012). Theory of Mind. Link: http://fas-philosophy.rutgers.edu/goldman/Theory%20of%20Mind%20_Oxford%20Handbook_.pdf.pdf

-

[5] Theory of Mind. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Link: http://www.iep.utm.edu/theomind/

-

[6] Mazza, M., Mariano, M., Peretti, S., Masedu, F., Pino, M. C., & Valenti, M. (2017). The role of theory of mind on social information processing in children with autism spectrum disorders: A mediation analysis. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(5), 1369-1379.