ML.rand() Part 1 - Synthetic Gradients and Decoupled Neural Interfaces

/ 6 min read

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on my LinkedIn (click here) on April 28, 2018.

Introduction

Welcome to ML.rand(), a brand-new series where we can discuss virtually anything about Machine Learning, randomly. As opposed to ‘On Generative Modelling’ series which is limited in terms of its subject matter, ML.rand() has much broader topics. In fact, it’s kind of a super-set of my previous series. I hope you enjoy it.

This is actually the first article of the series. Here we are going to be dissecting a paper [1] published in 2016 by Jaderberg, M. et al (2016) from DeepMind: Decoupled Neural Interfaces Using Synthetic Gradients.

Synthetic what now?

First of all, we need to understand that Neural Networks (mostly) learn by comparing the outputs to the true values in a dataset. Then, they try to compute the gradients and backpropagate them to adjust the weights accordingly in order to make the outputs more accurate.

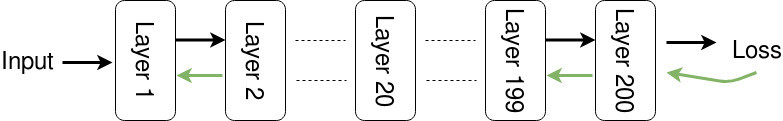

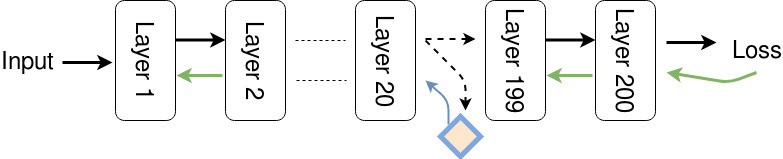

But did you know? during a learning cycle, before we can update the weights, all layers must be locked out until a series of a forward and a backward pass is executed. Let’s say we have 200 layers of FCN. Then the 20th layer should wait until the previous layers have been executed, to process incoming data. Moreover, the 20th layer should wait until the forwarded data reach the end of the network, the gradients are computed, and all layers next to it is updated (before its own turn to be updated). The same goes for each layer. They should be frozen and left untouched until they get the update signal, and this keeps going on until the learning process is completed.

These forwards, update, and backwards locking constrain us to running and updating neural networks in a sequential, synchronous manner [1].

This whole process is not so efficient. (or is it?). I mean, the amount of time spent for waiting a completed cycle until we get the update signal is considerably ‘huge’, and it is such a waste of time, right?

Imagine if each of individual layers of a network is able to guess what they think the data will say (guessing the update signal) the best they can and then they update their weights according to this guess. It means that each layer is able to learn in isolation and the training time can be reduced. How cool is that?

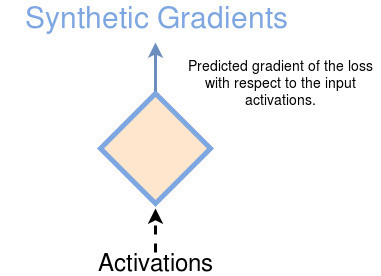

This best guess is called ‘Synthetic Gradient’ or SG for short.

SG allows layers or modules to be trained without update locking - without waiting for a true error gradient to be backpropagated. This ability of being able to update parts of a neural network asynchronously and with only local information was demonstrated to work empirically by Jaderberg et al (2016).

To sum it up, the goal of Jaderberg et al (2016) work was to eliminate update locking for Neural Networks by removing backpropagation. This resulting in what the authors called Decoupled Neural Interface (DNI) that allows each module to send messages in a way that these modules are update decoupled, e.g A does not have to wait for B to evaluate the true utility before it can be updated and A can still learn to send messages of high utility to B.

Removing Backpropagation? What?

Yes, you read it right. For those who didn’t know, yes, we can train a neural network ‘without’ backpropagation.

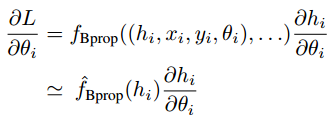

Note: equations are taken from [1].

In order to do that, the authors approximated the function implied by backpropagation. Basically, we won’t take into account the supervision y, inputs x, and weights theta in module i altogether, and just consider h which is the activations. With this approximate function, we can reduce dependencies and be able to update the weights of a particular module without waiting for the true gradients to be backpropagated with just local information h:

In contrast to other works that also try to remove backpropagation, Synthetic Gradients are able to eliminate update locking between layers. So, instead of waiting for the true gradients, a module (e.g layer) will predict the gradients with respect to current local information (about forwarded inputs) and update its weights without incurring any delay. Not only that, this work paving the way for multiple neural networks to communicate with each other or improving the long-term temporal dependency of recurrent networks.

If we have a synthetic gradient model, we can use the SG to update layer 20 before the rest of the network have been executed as follows:

So you say, we need a model to train a model?

Umm, yes. Synthetic Gradient Networks. And… we can train them as follows: First, remember that when we perform full forward and backprop, we will get the ‘true’ gradient. Then, we can compare this to our synthetic gradient in the same way we normally compare the output of a neural network to the dataset. In this way, we can train our Synthetic Gradient networks by pretending that our “true gradients” are coming from a dataset (a made up dataset, to be specific). Look at the following gif taken from a DeepMind blog to see how we train the network.

Man, what’s the point if we train the SG network using backprop?

Yeah, that’s exactly what I thought. Why would we want to train a network without backpropagation by using a network which trained with backpropagation? That will ruin everything, right?

But look at the above GIF closely. Do you find the answer? No? then look at the following image taken from the paper:

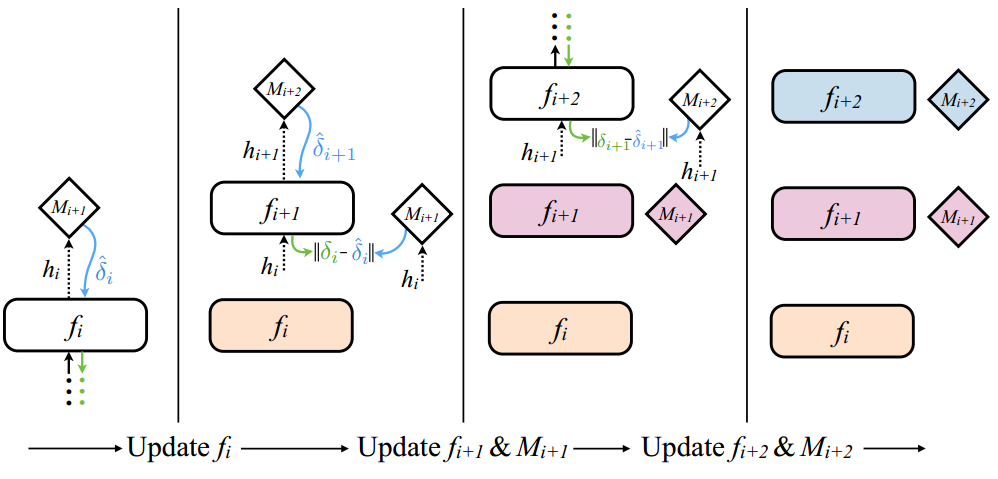

First, layer i executes it’s forward phase, producing hi, which can be used by Mi+1 to produce the synthetic gradient δi. The synthetic gradient is pushed backwards into layer i so the parameters θi can be updated immediately. The same applies to the next layers.

This means that each synthetic gradient generator is actually only trained using the Synthetic Gradients generated by the next layer and only the last layer trained using the real data. So, everything (except the last layer), including the Synthetic Gradient generator networks, is train based on Synthetic Gradients! Neat.

Final Thoughts

I personally think that Synthetic Gradient is cool. It allows us to train a neural network faster. Not only that, we can also train neural networks in a distributed manner which of course will eliminate the locking problem that is overly time-consuming or even intractable. We can also enhance the temporal dependency learn with RNNs, and speed up hierarchical RNN systems as empirically proved by the authors in their paper. If you are interested to learn more, go check the paper here.

Please correct me if you find something inaccurate, feedback on anything will be helpful!

References

-

[1] Jaderberg, M., Czarnecki, W. M., Osindero, S., Vinyals, O., Graves, A., Silver, D., & Kavukcuoglu, K. (2016). Decoupled neural interfaces using synthetic gradients. arXiv preprint arXiv:1608.05343.

-

[2] Czarnecki, W. M., Świrszcz, G., Jaderberg, M., Osindero, S., Vinyals, O., & Kavukcuoglu, K. (2017). Understanding synthetic gradients and decoupled neural interfaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:1703.00522.