Generative Modelling Part 2 - Adversarial Neural Cryptography

/ 8 min read

Disclaimer: This article was originally published on my LinkedIn (click here) on April 17, 2018.

TLDR; Using adversarial networks to decide how and what to encrypt. You have two nets communicating securely to each other and the third net wants to decipher that secure communication.

Introduction

This is the 2nd instalment of a new series called ‘On Generative Modelling’. In this article, we will continue our discussion about generative modelling.

Previously, we have learned about a type of neural network models called generative models which can be used to perform density estimation or generate new data points. These models try to understand the underlying structure of the data by themselves, potentially without any supervision. Then, with the acquired knowledge, they will be able to generate real-but-fake data.

We’ve also learned about how generative models (using a combination of a VAE and a GAN) can be employed to perform a video prediction task in one of Comma.ai’s publications. The study paving a way towards vision-based driving simulation which is super cool.

Now, we want to focus on a use case of generative models in cryptography world. We are going to be dissecting a paper published in 2016 by Martin Abadi and David G. Andersen from Google Brain: Learning to Protect Communications with Adversarial Neural Cryptography.

Whoa. What is that?

The authors started the study by asking a question, “Is it possible for a neural network to learn to use secret keys to protect information (from other neural networks)?”

Why do we want to do that? One might wonder.

It seems to me that the authors were just trying to ‘show’ us that neural networks can learn such a task. As neural networks are applied to increasingly complex tasks, they are often trained to meet end-to-end objectives that go beyond simple functional specifications. Be it to generate realistic images like the one we’ve discussed in the previous post or even to solve a multi-agent problem[2]. Now they want to train neural networks to protect information because why not? right?

So, yeah. Basically, what they were trying to do is to train neural networks to learn some cryptography stuff.

Neural networks for cryptography? Seriously?

I know that by now you must be sceptical because to the best of our knowledge, neural networks are generally just ‘meh’ in cryptography, you know what I’m saying. The simplest neural network cannot even compute XOR which is basics to many cryptographic algorithms.

But the study demonstrates that neural networks can learn to protect the confidentiality of their data from other neural networks and learn about encryption-decryption without being taught explicitly about any cryptographic algorithms. That’s very promising because sometimes it’s sufficient to protect information by just knowing how to encrypt[1]. What’s even more interesting is that neural networks can also learn WHAT to encrypt. So it is possible to prevent adversaries from seeing some parts of the data.

Cool, right?

But please note that this isn’t cryptography as you know it nor is it cryptography intended to actually be used to protect any “real” information. But still, cool and fun. Who doesn’t love something cool and fun?

OK, whatever. How to build one?

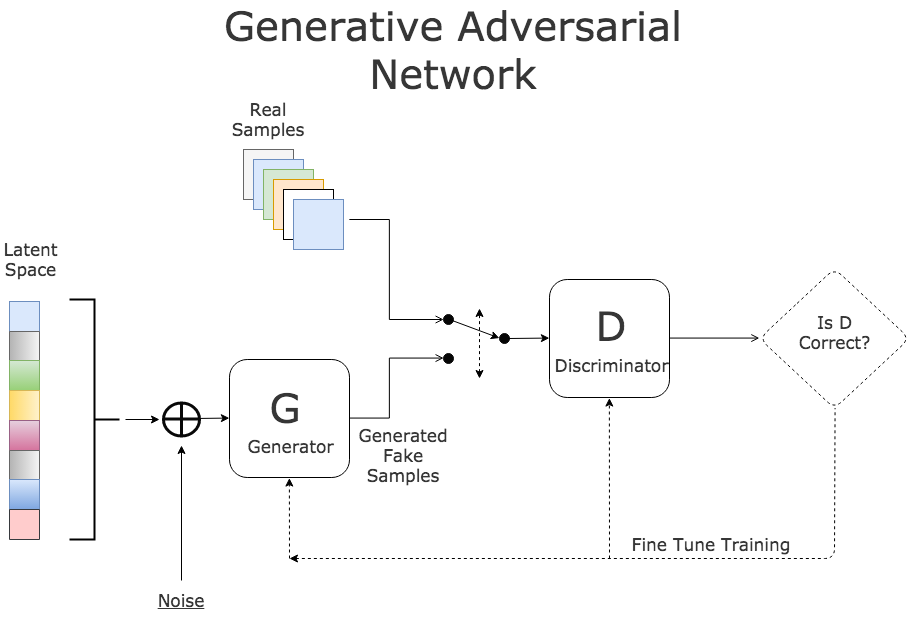

I briefly mentioned how Comma.ai tried to attack a video prediction task by coupling a GAN with a VAE[4]. It turns out the same neural networks can also be used in our task (with different architecture of course). But now, we want to train the GAN alone without the VAE.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [3] can be considered as the new cool kids on the block today. GANs is a branch of unsupervised machine learning implemented by a system of two neural networks competing against each other in a zero-sum game framework, namely the generator network, and the discriminator network. This could be anything, be it a sophisticated net like convolution networks or just a two-layer neural network. For more detailed information about GANs, you can learn from this article or come visit the original paper here.

The Setup

Our goal is to protect the confidentiality of a plaintext using shared keys.

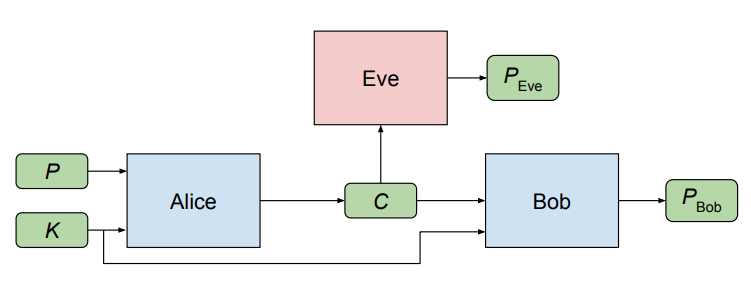

The authors set up their experiment as follows. We have three parties involved namely Alice, Bob, and Eve. Alice wishes to communicate an N bit message “P” (encoded as a vector of -1.0 or 1.0 values to represent 0 and 1 respectively) to Bob securely, so they share a key (which you can think of as a password) of N bits to preserve the secrecy of the message by encrypting and decrypting the message. Here, the length of the message equals the length of the password.

On the other hand, Eve does not have access to this key.

Note: “P” stands for the plaintext (the message), and “C” stands for the ciphertext. “K” is the key.

Alice takes the message + the key, and encrypts the message, producing a ciphertext “C” of N bits. Bob receives the ciphertext and then attempts to decrypt it, producing PBob. In addition, for every plaintext, there is one fresh key K.

Unfortunately for Bob and Alice, Eve intercepts Alice’s ciphertext “C”. She then decrypts this message herself, producing her attempted recovery of “P”, called PEve. Here, Eve can be thought of as the adversary.

Alice, Bob, and Eve are resemblances of neural networks and all three of these networks are quite similar.

Objectives

Eve’s goal is to reconstruct P accurately while Alice and Bob’s goal is to communicate clearly with high degrees of security so that no one but only them knowing the message. In contrast with common adversaries of GANs, in this scenario, Eve doesn’t have to distinguish “C” from a random value drawn from some distribution. Hence, we should reformulate Eve’s goal to distinguish the ciphertext constructed from two different plaintexts instead.

So, basically, we want to train Alice and Bob jointly to communicate successfully and to defeat the best version of Eve as in the definitions of GANs. It means Eve is not fixed and always learn over time. Then it is no surprise that sometimes Alice and Bob may not win the ‘competition’.

The Networks Architectures

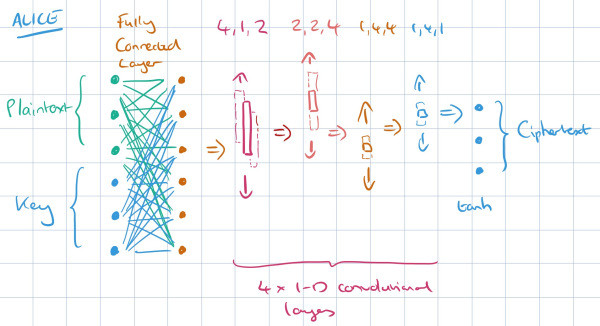

We chose “mix & transform” architecture in which the networks are consist of a fully connected layer followed by four 1-dimensional convolutional layers which together reduce the inputs down to an N-bit.

Alice receives and mixes the message + the key together to produce output called ‘ciphertext’ with the same length as the key and the message combined, as depicted above. Then she passes the ciphertext to Bob. Both Alice and Bob have the same network architecture, but as for Bob’s network, we use the ciphertext as the input and combine the key with this ciphertext instead.

Eve’s network is also quite similar to Bob and Alice’s. However, she only receives a ciphertext (without the key) and will be trained to reconstruct the message from the given ciphertext. She also has an additional fully-connected hidden layer of size 2N prior to the convolutional layers to make its network a bit more complex so she will be able to figure out the ciphertext.

Loss Function

So, these are the last things we need: the loss functions. In this setup, we have two different loss functions. Eve’s loss function and Bob + Alice’s loss function.

Eve’s loss function is the absolute difference between the message vector P and her attempt at decrypting it, called PEve. The loss then backpropagated through the weights in the Eve network to update her weights. The loss function can be written down like this:

Pretty simple, right?

As for Bob + Alice’s loss function, we will also compute a similar thing: the absolute decryption error. But with an additional term that signifies how well Eve is currently decrypting the message, so we have:

Putting these all together, we have:

Training Process

To train the networks, the authors use a “minibatch” size ranging from 256 to 4096 entries and Adam Optimizer with a learning rate of 0.0008. The training process alternates between Alice/Bob and Eve with ratio of 1:2, where one minibatch for Alice/Bob and two minibatches for Eve. With this, we can give a slight computational edge to Eve.

Umm, is there any code?

I am currently working on a PyTorch version of it and I think I will be able to release the code in a couple of days. Or weeks?

But you can check the Tensorflow version written by others, here.

Final Thoughts

Honestly, this work on adversarial neural cryptography by Abadi et al is thought-provoking and quite fun. There is also an additional section on learning WHAT to protect which is very interesting because with this, we can “Protect information selectively while maximizing utility”.

References

-

[1] Abadi, M. and Andersen, D.G., 2016. Learning to protect communications with adversarial neural cryptography. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.06918.

-

[2] Foerster, J., Assael, Y., de Freitas, N. and Whiteson, S., 2016. Learning to communicate with deep multi-agent reinforcement learning. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 2137-2145).

-

[3] Goodfellow, I., Pouget-Abadie, J., Mirza, M., Xu, B., Warde-Farley, D., Ozair, S., Courville, A. and Bengio, Y., 2014. Generative adversarial nets. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 2672-2680).

-

[4] Kingma, D.P. and Welling, M., 2013. Auto-encoding variational bayes. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114.